|

|

The World History Rewritten

Ancient Rome

Speaking about Ancient Rome there are two important problems

that have to be aforementioned:

- First, people usually have a quite good knowledge about

the history of Rome in times of late Republic (I-st century BC) and

history of Roman Empire after Caesar. But, as I mentioned before these

times Rome was no more a democracy, but a populistic country. And a

common knowledge about the history of democratic period of Ancient Rome

history (449 - 133 BC) is usually very poor.

- Second, we have limited historical sources about early

ages of Rome. Everything before year 500 BC is half-legendary (like

Lykourgos in Sparta). I think that most of

the facts in Roman chronicles are generally true, but it is my personal

opinion (that roots from laws presented here). Moreover, most of the

chronicles that describe the early ages of Rome were written in times

of late Republic, so are not always impartial.

To the

top

Populistic

Rome (509-449 BC)

Traditionally Rome was

founded in 753 BC by Romulus. Next

king Numa

Pompilius created the senate. Roman nobles (patricians) very

early gained political privileges and thus in times of Etruscan kings

(617-509 BC) Latin Rome was feudal state with extended political

institutions for nobles. This subclass of feudal system is called a

“feudal democracy”.

As I said before, Rome became populistic state in the year

509 BC when citizens of Rome banished Etruscan king Tarquinius Superbus, and after a very short

time (only 60 years after) in 449 BC Rome city-state became democratic

country.

What was the reason for so fast political evolution?

Well, here is “quick-and-dirty” explanation:

- First, feudal and

then populistic Rome have no place to expand because have many

strong neighbours: Etruscan city-states and Latin tribal states, so its

political system could not decompose because of too many conquered

lands. Moreover, for the same reason, the war was always was the worst

strategy of increasing wealth for Romans. Trade and export were more

profitable.

- Rome was important intermediary in salt trade that goes

thorough the city (which made merchant class stronger), and an exporter

of agricultural products (which turned Roman peasants into farmers).

- Rich Etruscan city-states these times colonized the

Northern Italy and were a great market to sell Roman agricultural

products.

Because of reasons mentioned above feudal

Rome under the rule of Etruscan kings became the

“feudal-democracy”. Etruscan kings have limited power

(probably were even elected by Roman nobles), and noble class

(patricians) had many political privileges. As the example of England

(1642-1689) proves, when the feudal state with “feudal-democracy” becomes

populistic,

very quickly turns into democratic country, if the external economic

conditions

are good.

After the banishment of Etruscan

kings (509 BC) Rome became a republic. It was a small

populistic city-state that waged many, but rather small wars in

close vicinity (no more than 50 miles from Rome), and its political

system evolved step-by-step evolve through many conflicts between

patricians (who ruled the city) and plebeians who had almost no

political rights at the beginning.

In 494 BC plebeians made the First Seccesion - they went out

from the city threatening that they will not work and fight for

patricians. With that “strike” they gained a special representation: plebeian tribunate - a few special

city-officials (or ombudsmen), who could negate the laws

created by Roman senate dominated by patricians, and have

political immunity (no one citizen could kill plebeian tribune).

That privilege made the further political struggle conducted by

plebeians against the patricians senate much easier. It useful to note

that this success shows the economic strength of plebeians. If

plebeians position had been weaker, they would have been pacified with

brute

force by richer citizens.

To the top

Democratic Rome

(449-133 BC)

With that institutional protection plebeians could fight for

their rights more effectively. Finally, after the 45 years of

(sometimes brutal) struggle, the populistic system ended. In

451 BC

the Commission of Ten was

nominated to write down law regulations which was demanded by

plebeians. These times courts (or law enforcement) were dominated by

patricians who often abused law against plebeians, taking advantage of

fact that law regulations wasn’t written down. But the 10 patricians,

who were nominated to the Commission, tried to rule Rome as long as

possible and refused to include plebeians postulates into a new codex.

So, in 449 BC plebeians made the

second secession that effected in a compromise between

patricians and plebeians, and the Laws of

Twelve Tables (lex duodecim tabularum) were legislated. With Valero-Horatian Laws (also 449

BC)

it was something like a Constitution and Law Codex of democratic Rome:

- regulated the political life of Rome

- regulated the legal system of Rome

With this dawn of democratic system (in 449 and in a few

subsequent years) plebeians gained also:

- law to marry with

patricians (since then patricians were no longer a closed social class)

- some guaranties and privileges for tribunes and for the

meeting of plebeians

- a law that prohibited to create a city office (institution)

from which decisions a citizen of Rome couldn’t appeal to some other

city institution (ius provocationis).

In other words: a

citizen should always have a right to appeal from arbitrary

administrative decisions.

|

Democratic system usually starts when different GPIs

(groups of political interests) have not enough power to dominate

other GPIs, not because of politicians become honest and intelligent or

country inhabitants become more mature. Democratic system is simply an

effect of a draw situation in the struggle for power.

|

Since then the polity of Rome were changed in an evolutionary

way. And finally after a many decades of political struggle (but waged

in democratic manner) plebeians acquired the law to be elected on every

city office (originally most of offices were accessible only for

patricians). It is useful to compare this evolution with the evolution

of Great Britain political institutions in XVIIIth and XIXth centuries

- Struggle of Orders between patricians andd plebeians resembles the

conflict between Whigs and Tories.

To be honest: usually in democratic manner. There were some exceptions.

For example in 439 BC a rich plebeians Spurius Melius, who presented

grain for free, buying this way a political votes for himself, was

killed by an army officer who had been ordered to arrest him.

|

Democratic system is not an utopia or ideal

system

It is rather a continuous, never-ending struggle to protect democratic

institutions against government abuses and manipulations (and sometimes

against the manipulations started by political opposition too) or

against the corruption. The criminal methods of making politics

sometimes happen in democratic system, but

are exception rather than the rule (opposite as in populistic system).

|

But generally the laws of twelve tables and political

institutions of Rome worked fine for over 300 years. And the higher

rationality of democratic system gave Rome an important advantage over

all of the neighbouring countries.

|

Democratic system is not free from brainwashing

ideologies

Of course in democratic system political ideologies have no such power

like in populistic country, but this doesn’t mean that ideologies are

not present in democratic country. Even in democratic system more than

95% of citizens are making their political choices under the influence

of some ideology. Overall effect is rational only because they believe

in

different ideologies.

Rationality of democratic system is an effect of a free market of

ideologies, an effect of freedom and pluralism in the world of

ideologies.

But under some conditions, (ex. when the dangerous or profitable war

comes), there is a chance that political life in democratic country

will be strongly saturated with ideology.

|

It is a good moment do describe shortly the system of democratic institutions of Rome.

It was quite complicated system (but no more than institutions of

European Union today), but well balanced and with many protections

against potential abuses. And please forgive me some terrible

simplifications I have made here, because of limited space:

- There were a several city offices that constituted the

administrational framework for the city, and had some built-in

protections against abuses:

- Every office came from election

- Every office (even dictator

nominated when Rome was in serious danger) had the limited tenure

- Important offices like consulate

(two officials that took the most important decisions

for the city, and command the Roman army) were collective, so one

official could control the another

- When the tenure ended, a citizen might not be

nominated for the same office for some time (usually for 10 years)

- There was something like the hierarchy of offices (cursus

honorum), so

politician who wanted to hold the highest offices was

first tested on less important offices

- And of course

no politician could hold two offices or hold an office

and be a senator the same time

- There was the senate of Rome (SPQR)

that was something like a higher house of parliament or a government.

The members of the senate were former city officials.

- There were a number of institutional guaranties which

protected the civil rights of every

citizen: ius provocationis, immunity of plebeian tribunes, independent

courts, legal system rooted from Laws of Twelve Tables. These

guaranties

had similar function as British Bill of the Rights or Amendments to the

Constitution of USA.

- There were four

different kinds of citizens meetings:

- concilia plebis.

Meeting of poorer citizens. A counterbalance for the senate. Had a

right to elect plebeian tribunes and other plebeian officials plus

some legislative privileges.

- comitia tributa.

Meeting of all citizens organized according to administrational

districts. The most democratic meeting. Most of Roman laws (called

“lex”) were legislated here.

- comitia curiata.

The older kind of meeting without great importance in times of

democratic Rome. Probably have (aside of the other responsibilities)

the same responsibilities as the High Court or the

Constitutional Court.

- comitia centuriata.

Meeting of citizens organized by the types of military units they

belonged to (and the types of military units corresponded with the

social status of different groups of citizens). Dominated by

patricians, who had privileged representation here. This meeting

elected higher city officials.

It is useful to note here, that in spite of privileged

position that patricians had in senate and in the comitia centuriata,

since

the early days of democratic republic a plebeian could be elected even

to

the highest office (i.e. could not became a consul, but a “military

tribune” who generally had the same scope of authority).

And with the permanent political conflict between plebeians

and patricians (which is typical in democratic states), Rome was

surprisingly strong. Ironically it was thanks to this permanent

conflict which forced Romans to solve potential social problems before

that problems become serious. This is one of the most important

strengths of the democratic system.

|

Political power in a democratic system usually

is not equally distributed

When there is a group (GPI) of 10% richest citizens that group usually

has more than 10% share in political life of democratic country. There

is nothing strange here, they simply have greater political strength

than other groups of citizens. The same is true for educated citizens,

they

are also over-represented in political life (comparing with their

number).

This is not honest or righteous, this is effective.

- When political interests low-income citizens are

over-represented, the rate of development is slower, and that country

have not enough capital resources to compete successfully with other

countries, either on economic nor political and military planes.

- When political interests of upper-income citizens are

strongly over-represented, the costs of protecting a very unfair

redistribution of wealth are too high (and the risk of social unrest is

very high) making the country’s economy ineffective too.

So, democratic country is effective because it maintains the balance. |

Of course Rome was not a democracy like democratic countries

today. Times and people’s mentality has changed, and technological

advances made present democracies more “people-friendly” and wealth

distribution more righteous. Honestly, there is even a great difference

between democracies today and before 1968. But comparing with any other

ancient state, ancient Rome was the country of political freedom and

much safer place to live.

To the top

Why

Rome built an empire?

Now it is time to explain shortly, why

Rome built a great empire. But first I have to correct one

false image that many people have about ancient Rome.

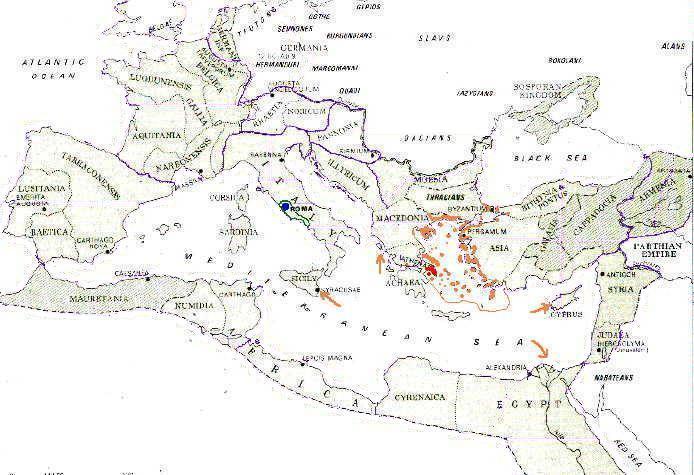

People generally think that Ancient Rome was as a very

militaristic state. It’s not true. Let see a map that compare Rome and

Athens states about 440 BC Just after Rome changed to democratic

system and just before the Peloponnesian War in Greece, when both

countries have more or less

the same population (150 - 200 thousands of citizens).

Athens and Rome 440 BC I have

lost the link to the Web site where this map comes from. Please

take my apologies.

Rome city-state is marked blue.

Athens city-state is marked red

and its colonies in Athens Sea Union are marked orange.

Orange arrows shows the

farthest operations of Athens fleet (with troops on board) during the

Pelloponnesian War and before

(in the age of Pericles).

And thin green line shows borders

of Rome 327 BC, just before Alexander the Great conquests in Persia

that changed economic conditions for whole Mediterranean and Middle

East.

As you can see, comparing with Athens, and with almost any

populistic city-state in the Mediterranean region, Rome was rather

peaceful, non-expansionistic state. Actually, a great part of Roman

conquests at the early stage of its expansion were the effect of devise

“si vis pacem, para bellum” (you

want

peace, be prepared to wage war) - Romans simply eliminated the

potential threats to their state.

Generally a

320 years long expansion of democratic Rome was possible because of

five reasons:

- First, Rome was democratic, so ruling GPI (group of

political interests) could not involve the state into a war that would

give profits only that GPI, when other GPIs had to pay costs of that

war. All costs of every war were evident, no cost were hidden. So, Rome

waged only those wars which were necessary because of national security

reasons, or were profitable for most of the citizens.

- Second, Rome used

only a small percentage of its resources in expansive wars. So, when

the city was in real danger (as the war with Sammites, with Pyrrus or

with Hannibal), Rome could loss a dozen of battles, and always had

reserves to build another army. (Compare this with great industrial

production increase when USA joined the 2nd World War.)

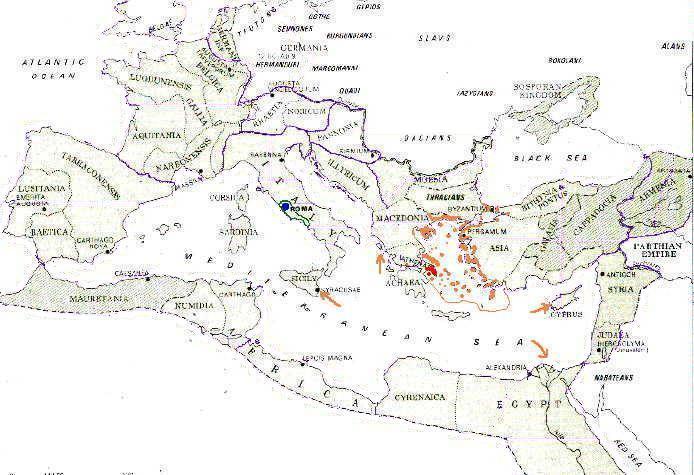

- Third, Rome almost always built an alliance against its

enemy with some other states (even if Rome was actually stronger).

About half of the Roman Empire were really the allies of Rome -

countries or tribes that were united with Rome in more or less peaceful

way (see Map). It is useful to mention here two

basic rules from diplomatic games:

- Even much stronger enemy can be defeated by the alliance

of smaller states

- When there are several players, is often no chance to win

anything without making an alliance

- Fourth, Rome very

quickly adapted and imported technologies from neighbouring countries.

Most of the Roman war tactics and military technologies were taken from

its enemies.

- Fifth, divide et impera

(divide and rule). (divide and rule). One of the basic tactics that

lowers the costs of occupation of a country is to find here an

important GPI (conflicted with other GPIs) which will support the rule

of the occupier and pay some costs of occupation. It is very easy to

find that group in a feudal country, rather hard in a populistic

country, and almost impossible in a democratic country. Therefore Rome

could use the tactic of divide and impera against almost any enemy, and

no enemy could use this tactic against Rome.

|

Democratic system is a very dangerous enemy

Generally, democratic country loses a war only when it have to retreat

from colonies that had became to expensive to control (like United

States for England or Algeria for France).Of course there are no rules

without exceptions. There was

one war that was completely lost by democratic country: in 390 BC a

Rome was defeated and occupied by Celtic tribes.

|

And now is a good time for a short digression. I have written

that science and technology development is faster in a democratic

country than in a populistic one. But we all know that Greeks made much

more discoveries than Romans. Are you wonder why? Here is a

quick-and-dirty explanation:

- There was many Greek city states and only one Rome

city-state.

- At the beginning Rome had quite low technological level, so

more profitable choice was to import technologies from Etruscans and

Greeks.

- Romans invented many new technologies which was not so

spectacular as Greek discoveries but had important impact on everyday

life (ex. in road and bridge building, construction, law system). We

don’t call people like James Watt, Thomas Edison or Steven Wozniak

great scientists but their inventions launched great changes in our

life.

- When Rome achieved technological level comparable with

Greece, it was so strong country that the state investments (i.e.

expansive wars) started to be more profitable than science development.

Then in a very short time Rome became populistic state.

As you can see, even very strong law of history could be (under some

circumstances) negated by a cumulated effect of other laws. It is one

of the reasons, why the overall pattern of our history is so

complicated.

To the top

Collapse of

democracy, populistic Rome again

With all conquered lands, the polity of Rome still was the

same as

when it was a small city-state. Conquered provinces were administrated

by former city officials or special private enterprises. Romans usually

confiscated from 1/3 to 2/3 of fields from countries they had conquered

(Athens usually confiscated the whole land). These fields then became a

property of Rome called ager publicus

(public land). This land was divided between the citizens of Rome, who

organized here farms or plantations.

In the middle of IInd century BC the great conquests of Rome

(whole Italy, Spain, Greece, North Africa, Mediterranean coast of

France, coast of Adriatic Sea and western portions of Asia Minor)

started two important processes:

- First, a cheap import of agricultural products from newly

conquered lands and Egypt started the agricultural crisis in Italy.

Many owners of small farms bankrupted, and migrated to the city of Rome

where they have better chances to survive the crisis. Rich planters

increased the exploitation of slave-workers.

- Second, rich citizens grew in wealth, because they have

better starting position in the race for profits that great conquests

of Rome had brought: they could gain a larger farms made from ager

publicus, and have a better chance to gain a privilege of

administrating the conquered provinces, which was extremely profitable.

This way the GPI

(group of

political interests) of the richest

citizens grew in strength, and many very poor citizens arrived to

Rome increasing the number of poor educated citizens with

no financial independence (because of low-income) who were easy to

manipulate by populist leaders. The group of middle-income citizens

became overpowered, and that was the economic reason

for the fall of democratic

system in Rome.

GPI of richer citizens formed a faction of Optimates (represented by

the senate), and the leaders of poor citizens formed the faction of Populares (represented by

plebeian tribunes). At the beginning both factions competed in

democratic manner but about 133

B.C a leader of Populares and a plebeian tribune Tiberius Sempronius

Gracchus tried to promote an

legislation that introduced the agricultural reform: project to divide

great farms formed from ager publicus, and gave that land to poor

citizens. In counter-strike armed senators killed him and many men from

his faction on Forum (a central public square in Rome, the place of

political meetings).

The year of 133 BC was

the moment when democratic institutions of Rome were definitively

broken. So, I am nominating this year as the end of 315 years long

democratic period in the history of Rome. Of course it is an arbitrary

date. Whole process was gradual, and the economic base for democracy

decomposed probably a few years (or even decades) before, but

democratic institutions suspended the final fall of democracy until 133

BC.

The final element of diffusion caused by conquests of Rome was

the war with Roman allies in Italy (90-89 BC). In consequence of this

war Rome had to grant a privileges of citizens to all free people

living in Italy (with edict called lex

Julia after young Julius Caesar, who promoted that law).

Since then, the core of Empire was the whole Italy, not only the

city-state of Rome.

Because of economic changes, no matter which politician, or

which political option would won, the final result would be the same:

some kind of populistic

system. Further military expansion was the most

profitable way to increase national income, so finally the

populistic system in Rome took a form of military dictatorship.

|

Political clientelism

When the group of poor citizens is very large, they don’t represent

their own political interests but the interests of some other, richer

or more influential citizens. They are usually poor educated, with no

work or any stable source of income, what made them very susceptible to

manipulation by skillful demagogues, populistic ideologies or easy to

bribe with relatively small sums of money or cheap gifts. They become

clients of some other GPI or a populistic political party,

organization, church, charismatic leader, etc.

Term clients

come from the history of ancient Rome. During the first populistic

period (509-499 BC) rich patricians families were usually supported

by group of financially dependent clients. But there are other forms of

political clientelism too:

- Politicians

could buy votes for food (like Spurius Melius mentioned

before or Julius Caesar) or for alcohol (like in Kansas in

the early XXth century or in modern Russia).

- Local oligarch could threat them to vote for him, if

he have someway a control over their source of income (ex. could stop

their wages).

- Political party like communists in Soviet Union (or

some GPI of government administrators) could gain their votes offering

social protections and material stability, even if their wages would be

relatively low.

etc.

Ironically, because of the danger of political

clientelism, sometimes voting rights in democratic country could be the

privilege of smaller group of people than in some contemporary

populistic countries. Compare for example France and Great Britain in

the last decade of XVIIIth century.

One of the symptoms of increasing problem with political

clientelism could be a high popularity of primitive entertainments like

gladiator fights. Therefore it is always useful to observe changes in

culture, because this gives us a chance to predict social and economic

processes we cannot measure statistically for some reasons.

|

Populistic Rome was still the largest and strongest country in

Mediterranean region, so could continue military expansion with ease

for next 150-200 years. Until too high costs made that expansion

economically ineffective. Basically there was three elements of these

costs:

- Costs of occupying many large (i.e. with numerous

inhabitants) countries and protecting a very long border. These are

more or less the logistic costs, as Paul Kennedy describes them.

- Decreasing country's income because of crisis that was

launched by diffusion powers.

- Increasing costs of continuous wars with barbarians who

grew in number and strength (effect of importing Roman military

technologies) because of the same diffusion powers.

Diffusion powers launched by Roman conquests were responsible

for one of the longest economic recessions in history. Of course this

crisis had some intervals, and the same time some provinces like Gallia

(France) or provinces in Asia could experienced periods of economic

growth thanks the implementation of Roman technologies and the law

system.

To the top

Further

decomposition, feudal Roman Empire

About the end of II century AD political system of Roman

Empire regressed from from populistic

to feudal. As

with the fall

of democracy, is hard to give an exact year date here, because it was a

gradual process. I can only say this was happened probably between year

180 AD (death of imperator Marcus Aurelius at the end of serious wars

with German tribes of Marcomans) and the edict of emperor

Caracalla (212 AD) which granted citizen status to all free

people who lived in the Empire. That way emperor Caracalla gained extra

money from new citizens.

Here is a quick list of a few important processes we can

observe in falling Roman Empire:

- Because of economic crisis income from taxes shrank. That

forced Rome

Emperors to increase taxation and to spoil the money (decrease the

amount of precious metals in coins - a historical receipt to start

inflation which always helps to finance government spendings).

Unfortunately the side-effect of inflation is always the destruction of

credit system plus the higher transaction costs of every trade

transaction.

- Because of the fall of the trade, economic power of the

cities declined. And many richer citizens moved to rural areas to avoid

high taxes and other tributes for the state.

- Slavery production on large plantations became less and

less effective because of shrinking trade, increasing costs of capital

and workers resistance. Therefore, large land owners started to prefer

small farms with feudal-dependent peasants over the

organized slavery plantations.

- Rome as the rich state was an immigration destination

country for many barbarians, a long before their forces invaded Roman

Empire. It was very similar process like Muslim

immigration to EU, with the same social and political consequences, but

of course the scale of immigration in Ancient Rome was

greater.

- Social processes like: shrinking of the liberal-oriented

middle-class (and thus decay of rational ideologies promoted by that

class), long lasted economic crisis plus natural disasters launched by

that crisis (like great plague in the last decades of

II century), and need for ideology that could cement the resistance

against government and economic oppression - all those reasons

increased the popularity of different religions

(cults of Kybele, Isida, Mitra, etc.) imported from the East.

Change from populistic to feudal system in a short run increased the

military power of Roman Empire, but couldn’t stop the diffusion

processes, so the final fall of the Empire was unavoidable.

Long-distance trade which glued the state shrank so much that the

Empire finally broke into a few pieces (which was the beginning of

feudal fragmentation). Eastern part of the Empire (Byzantium) which was

composed of mostly civilized lands, survived the crisis, but the

Western part that consisted of many less-developed lands conquered on

barbarians was completely destroyed by the

invasions of

German tribes in the Vth century AD.

Final Notes on Ancient Rome

Generally, first chronicles that are

describing the history of the beginnings Rome were written in Ist

century BC when Rome was populistic or at best in IInd century B.C,

when the democratic system of Rome was decomposing. Ancient historians

were not always objective (impartial), and they obviously weren’t know

for sure some facts from the first centuries of Rome (especially

because some documents were lost in the time of Celtic invasion - 390

BC). Moreover, many parts of later historical documents and chronicles

were lost too. So, you have to be aware that facts from the democratic

period of Rome history are not always certain.

For example I know two variants of history of Spurius Melius. Which one

is true? On the other hand, statistical information about the number of

Roman citizens are precise because were systematically collected by the

democratic administration of Rome, and the number of citizens of

ancient Athens we can only guess.

Warsaw, 18 November 2003

Last revision: July-August

2006.

Slawomir Dzieniszewski

|